Rock to jolt stagger to ash

27

CREDITS

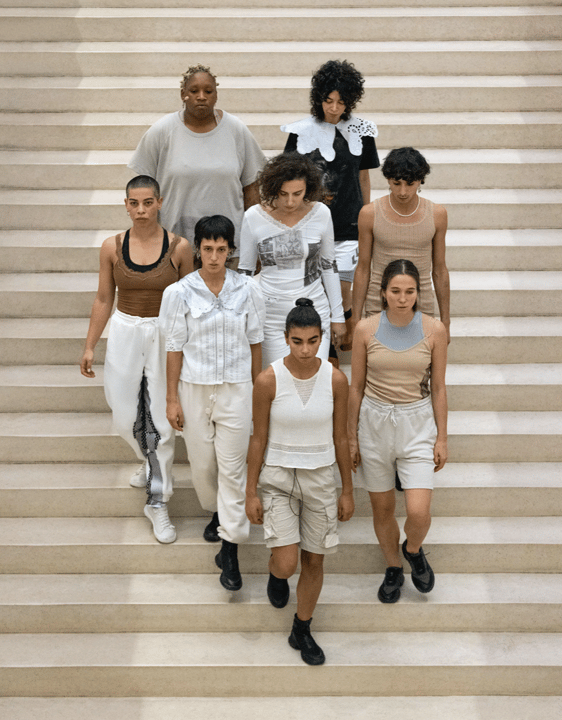

CONCEPT, CHOREOGRAPHY, COMPOSITION, DIRECTION, TEXT: Alexis Blake

GRAPHIC DESIGN: Sandra Kassenaar, Dongyoung Lee

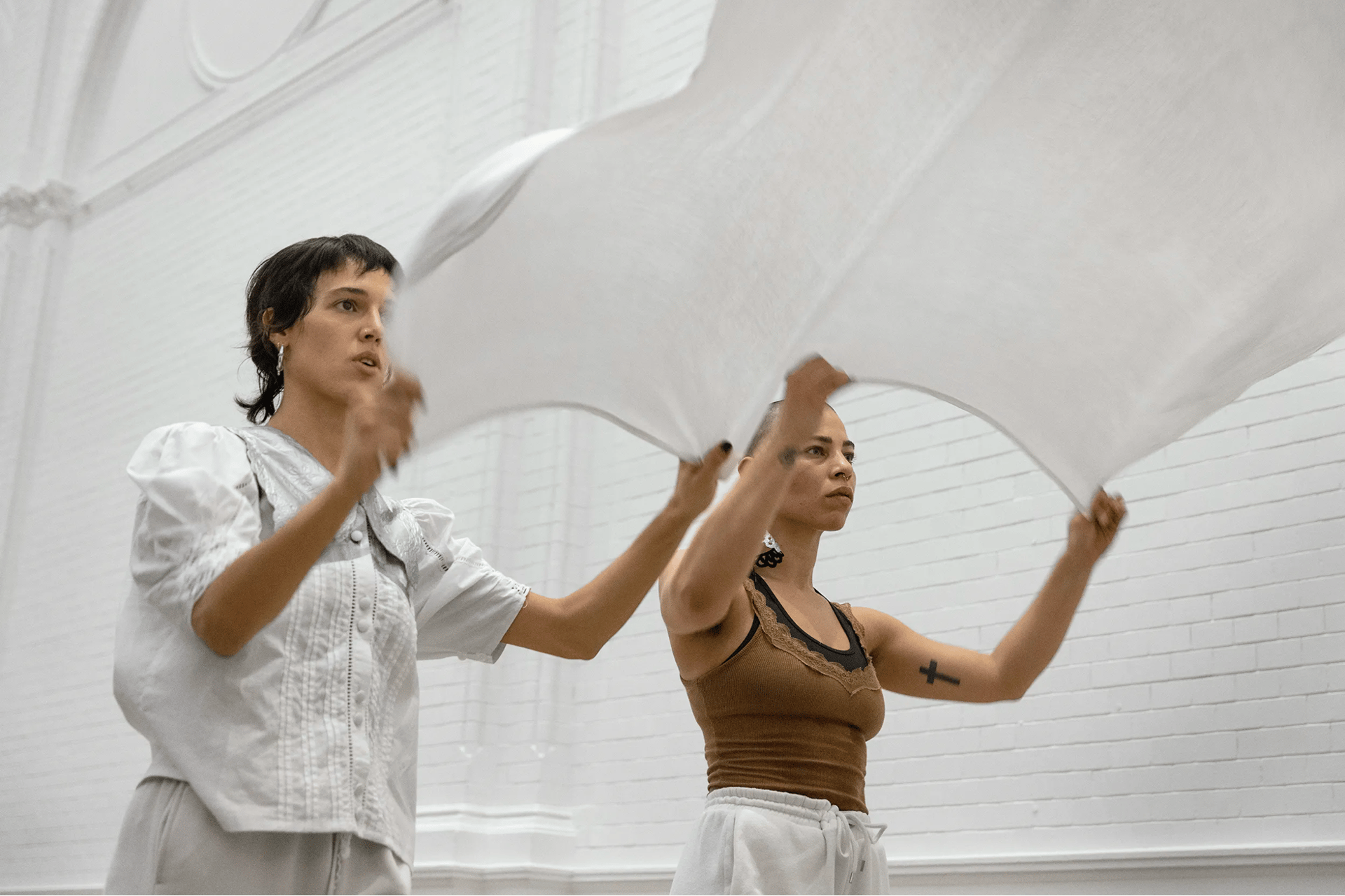

GARMENTS: Elisa van Joolen with Mika Perlmutter

SMELL: Sissel Tolaas

DANCERS (choreographic input /performing): Shari Ashley Labadie, Alice de Maio. Polina Mirovskaya, Gianine Strang

SINGERS / COMPOSERS: Sanem Kalfa, Logan Muamba Ndanou

SOUND ARTIST /COMPOSER: Ghaith Qoutainy

SOUND ENGINEER: Hala Namer

SWINGING SPEAKER: Hala Namer, Ghaith Qoutainy

PRODUCER: Helena Julian

PRODUCED BY: Stedelijk Museum

CURATOR: Britte Sloothaak

SOMATIC THERAPIST: Amanda Macrae

SUPPORTED BY: The Mondriaan Fonds, Outset Contemporary Art Fund

rock to jolt [

] stagger to ash was realised for the Prix de Rome Visual Arts 2021

Poem fragments in text : If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. Translated by Anne Carson. New York: Vin- tage Books, 2002.